|

All about magic lantern slides |

|||

|

PART 1: PART 3: |

MANUFACTURING THE SLIDES

The use of shadows (silhouettes) was otherwise known already

prior to the introduction of the Magic Lantern. In the first stage also Athanasius

Kirchner used jumping jacks, cut out letters, devil's heads and even living flies in his

primitive magic lantern, just for the purpose of creating silhouettes. This conception,

placing black, non-transparent pictures on a transparent bottom layer, was probably also

applied with the first lantern-slides. Glass was mainly used as a bottom layer, but the painting was

also carried out on oiled paper. At first only silhouettes were painted with black paint,

The light sources of the very first magic lanterns were very

weak: a candle or a little oil-lamp. The designers succeeded in showing

Around 1820 the magic lantern and -slide industry started developing favourably. Philip Carpenter, partner of the British company Carpenter and Westley, worked out a technique to produce slides machine-made. The outlines (contours) of the figures to be painted, were graved into copper plates, thereafter the areas were coloured by hand. This period marks the transition of the hand-made production of slides to mass-production in the industrial era. In Germany hand-painted slides were made by Liesegang in

Dusseldorf, Talbot in Berlin and Unger & Hoffmann. The London companies of Newton

& Co and E.G. Wood applied modern production methods resulting in a sales-figure

between 150.000 and 200.000 slides. As themes often horror images (the devil, death) and 'topics of the day' as well as historic events (the Great Fire of London in 1666) were used, but 'naughty stories' also proved to be most popular (indeed, there is nothing new under the sun). |

|

Decalcomania With the introduction of the glass-negative enabling the production of 'photographs on glass' , the use of decalcomania for slides was not negatively effected. Printing off in colours was not yet possible at that time. Only during World War II the decalcomania-technique gradually had to make room for the photographic colour-slide, the same as we still know to day. | ||

|

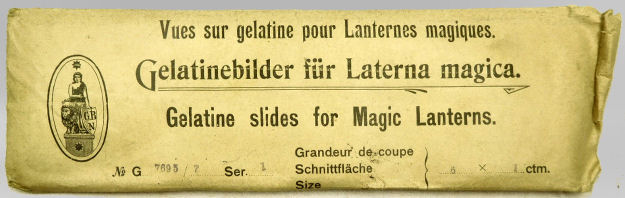

The decalcomania were usually delivered 'ready to

use', stuck on the glass, but there were also sheets of stickers on the

market for do-it-yourselfers. The Gelatinebilder were manufactured and sold by Gebrüder Bing Nürnberg. The envelope bears the trademark of G.B.N. printed, which was used from 1890-1906. The images on the gelatine sheets were the same as those on the ready-made glass lantern slides released by Bing. |

|

|

|

||

|

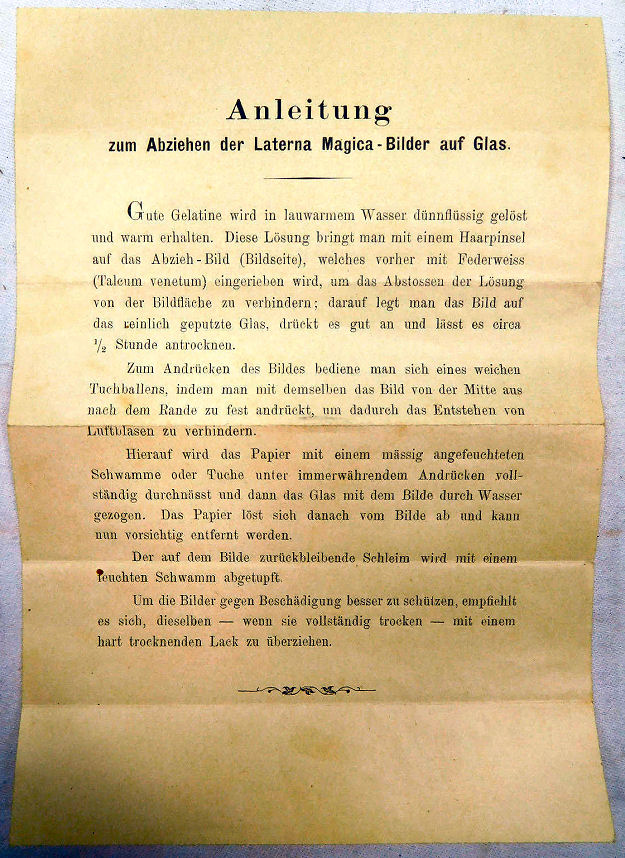

Instructions for transfering the Laterna Magica images on glass. The gelatine is thinly dissolved in lukewarm water and kept warm. This solution is applied with a soft brush to the image strip to be peeled off (image side), which has been previously rubbed with talcum powder (Talcum venetum) to prevent the solution from spreading from the image surface. Then place the image on the cleaned glass, press it firmly and let it dry for about half an hour. To press the image, use a soft wad of fabric by pressing it firmly from the centre to the edge to prevent air bubbles from forming. The paper is then continuously soaked with a moderately damp sponge or cloth while being pressed continuously and then the glass containing the image is drawn through water. The paper then dissolves from the image and can now be carefully removed. The slime that remains on the image is removed with a damp sponge. To better protect the images from damage, it is advisable to cover them with a hard-drying varnish as soon as they are completely dry. |

|

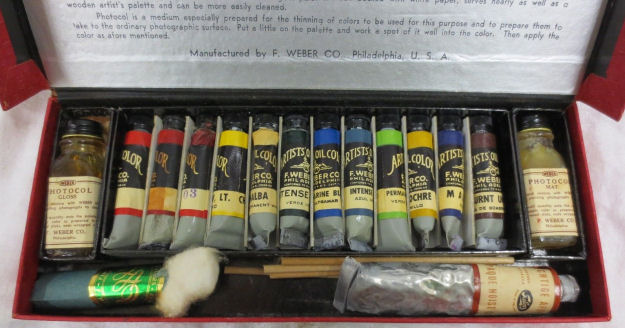

| Various manufacturers also sold a special colouring box for colouring lantern slides, including tubes of transparent paint and brushes, suitable for painting from scratch or for touching up damaged slides. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

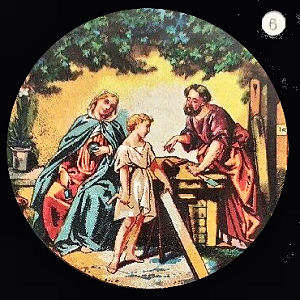

The subjects they dealt with were quite different. Most favourite were the 'living figures' , some sort of 'tableaux vivants' with which full stories were depicted. The living beings are playing against a decorated background, but likewise in the open air. Especially bible stories were performed in this way, complete with a living ox and donkey, and put in a European landscape. Famous works of art, masterpieces (sculptures and paintings)

as well as illustrations from books or periodicals were depicted too. Many series were

dedicated to far away countries and towns, in those days it was often the only possibility

to view an unknown foreign In catalogues published after 1900 we can also find 'photograms'. These were finely finished drawings which had been multiplied photographic ally by means of contact printing. It looks as if editors did not worry that much about the original artist's copyright. Almost everything that was fit to publish in books, magazines or newspaper, could serve as a subject for a series of lantern-slides. |

||

|

|

More about lantern slides..... |

|

|

©1997-2024

'de Luikerwaal' All rights reserved. Last update: 16-04-2024. |

|

and by whom lantern-slides were

made at the starting time of the Laterna Magica. The vulnerable glass-plates have not

outlived the centuries, whilst 17th century's descriptions and pictures deal more with the

apparatus, the magic lantern, than with the projected pictures. Probably the people who

carried out experiments with such plates, made the same themselves.

and by whom lantern-slides were

made at the starting time of the Laterna Magica. The vulnerable glass-plates have not

outlived the centuries, whilst 17th century's descriptions and pictures deal more with the

apparatus, the magic lantern, than with the projected pictures. Probably the people who

carried out experiments with such plates, made the same themselves. but very soon paints in different colours were also applied. Of course, the use

of transparent colours was indispensable; Naples Yellow, Prussian Blue and carmine, just

to mention a few, were most appropriate for this purpose. By way of protection, a layer of

transparent lacquer was spread over the paint; at a later stage they made use of a second

glass, i.e. a cover glass, as well (also see:

but very soon paints in different colours were also applied. Of course, the use

of transparent colours was indispensable; Naples Yellow, Prussian Blue and carmine, just

to mention a few, were most appropriate for this purpose. By way of protection, a layer of

transparent lacquer was spread over the paint; at a later stage they made use of a second

glass, i.e. a cover glass, as well (also see:  the pictures better by painting the part of the glass plate left around the

painted figures with black paint, thus preventing the light from shining through.

Originally the slides were made by the lanternists themselves. Also the instrument makers

and opticians producing and selling magic lanterns, mostly painted the accompanying slides

themselves. Later on this occupation developed into a trade apart. Painters were specially

educated for making the hand-painted pictures in companies which were receiving orders

from the manufacturers of magic lanterns. It was a kind of work requiring utmost accuracy,

for the slightest errors were magnified mercilessly. Although there are real masterpieces

among these hand-painted pictures, in spite of that it occurred very seldom that an artist

signed his piece of work.

the pictures better by painting the part of the glass plate left around the

painted figures with black paint, thus preventing the light from shining through.

Originally the slides were made by the lanternists themselves. Also the instrument makers

and opticians producing and selling magic lanterns, mostly painted the accompanying slides

themselves. Later on this occupation developed into a trade apart. Painters were specially

educated for making the hand-painted pictures in companies which were receiving orders

from the manufacturers of magic lanterns. It was a kind of work requiring utmost accuracy,

for the slightest errors were magnified mercilessly. Although there are real masterpieces

among these hand-painted pictures, in spite of that it occurred very seldom that an artist

signed his piece of work.

Initially this technique was used for decorating chinaware, later on also for

slides. Also in this case, in the first stage, only the figure-contours were printed on

the glass-plate, which was hand-coloured afterwards. For this purpose stencils were used

as well. Various techniques were developed to fix the drawings onto the prepared

decalcomania-paper. At first engraved or etched copper or zinc-plates were in use; later

on, after lithography had been invented, limestone too. The last enabled the

printing in colours.

Initially this technique was used for decorating chinaware, later on also for

slides. Also in this case, in the first stage, only the figure-contours were printed on

the glass-plate, which was hand-coloured afterwards. For this purpose stencils were used

as well. Various techniques were developed to fix the drawings onto the prepared

decalcomania-paper. At first engraved or etched copper or zinc-plates were in use; later

on, after lithography had been invented, limestone too. The last enabled the

printing in colours. transparencies were being made. After 1874, when they began to work with dry plates, this

process just got going successfully. In 1864 Walter Bently Woodbury was granted a patent

on the method of making a relief from an original photo-negative, in bi-chromatic

gelatine. This relief was pressed, by exertion of continuous

force, onto a leaden plate in order to make a mould of it. With such a mould it was

possible to produce 120 copies per hour. After 1890 the Woodbury-printing was being

replaced by mechanic reproduction methods enabling the preparation of half-tones as well.

Besides in black-white the transparencies were also supplied in stain- or sepia colours.

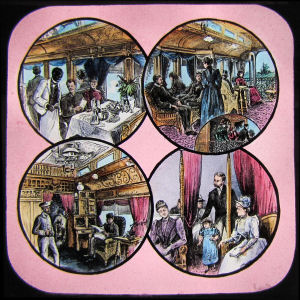

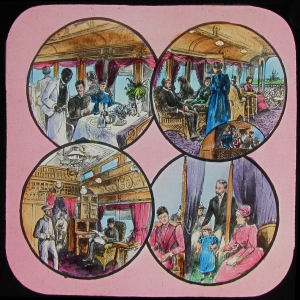

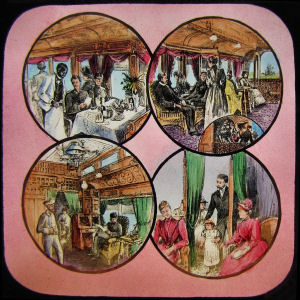

Sets of slides were usually released in two different versions, a black and

white version and a version coloured by hand with transparent paints. The

latter was of course a lot more expensive because colouring required quite a

bit of manpower and time. This tinting of the slides was always done by

several people and they were free to choose the colours they used. It could

happen that the main character wore a red dress in one series and a green

one in another. This was sometimes difficult when a slide was broken and was

replaced by a slide from a different series. Then it could happen

that even within one and the same series people suddenly dressed

differently. The pictures below clearly show this freedom of colour choice:

transparencies were being made. After 1874, when they began to work with dry plates, this

process just got going successfully. In 1864 Walter Bently Woodbury was granted a patent

on the method of making a relief from an original photo-negative, in bi-chromatic

gelatine. This relief was pressed, by exertion of continuous

force, onto a leaden plate in order to make a mould of it. With such a mould it was

possible to produce 120 copies per hour. After 1890 the Woodbury-printing was being

replaced by mechanic reproduction methods enabling the preparation of half-tones as well.

Besides in black-white the transparencies were also supplied in stain- or sepia colours.

Sets of slides were usually released in two different versions, a black and

white version and a version coloured by hand with transparent paints. The

latter was of course a lot more expensive because colouring required quite a

bit of manpower and time. This tinting of the slides was always done by

several people and they were free to choose the colours they used. It could

happen that the main character wore a red dress in one series and a green

one in another. This was sometimes difficult when a slide was broken and was

replaced by a slide from a different series. Then it could happen

that even within one and the same series people suddenly dressed

differently. The pictures below clearly show this freedom of colour choice: country.

Spending holidays abroad or TV-programmes

were yet unknown at the time.

country.

Spending holidays abroad or TV-programmes

were yet unknown at the time.